Secrets of making knives: from choosing the steel grade to the production method

When humanity began to hunt in ancient times, the question of cutting up animal carcasses arose. The knife was invented for this purpose. making played a big role in the culture of many peoples.

Nowadays, knives are produced both industrially and privately by blacksmiths and knife makers. If desired, today you can make a knife yourself, having the necessary materials and equipment.

When the desire and need for a knife arises, you need to decide what functions it will be intended for. This will affect the shape of the blade and handle. Depending on the purpose of the knife, both the appropriate materials and the method of sharpening the knife are selected.

Parameters of a quality knife

Making hunting knives is a special skill. A tool can become a reliable companion for a hunter, it is important if it meets the necessary requirements: the steel is hard and durable, the blade corresponds to its purpose in shape and sharpness. The handle should be comfortable, not slip in the hand, and not injure it.

The peculiarity of the metal is its combination of strength and hardness. In order for a product to have a long service life, it is necessary to find a relationship between these properties. If the steel is very strong, then its hardness will be low and, conversely, the harder the alloy, the more brittle it will be. The best product is considered to have a balanced combination of them.

Types of knives

Knives can be divided into several groups:

- kitchen - for cooking at home;

- stationery - opening envelopes and cutting paper;

- camping - with a more durable blade that performs rough work: cutting branches, preparing a fire, and the like;

- hunting - for easy cutting of prey;

- decorative.

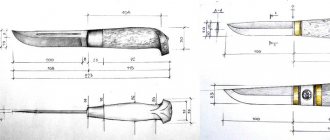

Knife making usually starts with a design, regardless of the manufacturing conditions. When choosing a knife, you need to consider that the handle is comfortable and holds the blade securely. The blade makes up the main part of the knife and can be made using different technologies.

The shape of the knife blade can be varied, upturned and curved upward, looking down (Finnish type), sharpened with a double-sided blade.

Blades are either solid or welded. The simplest manufacturing technology is considered to be all-steel and all-iron knives.

Welded blades can be made of iron or steel. Technologies for the use of three-layer steel, which have been known since the times of ancient Rus', are actively used in the production of knives by many modern European and Japanese companies.

The handle of the knife should be comfortable and securely held in the hand. According to the installation of the handle there are:

- end-to-end;

- mounted;

- invoices.

In the production of knives, the following materials are often used for handles:

- tree;

- birch bark;

- plastic;

- skin;

- micarta;

- artificial materials.

A high-quality handle must not only be comfortable to use, but also have an aesthetic appearance, complementing the blade, being in the same style with it.

By using classic and modern materials in the production of knives, you can create a real work of art.

Production technology

Despite the differences, the process of making knives has common technological components, strict adherence to which allows us to obtain a high-quality product. All operations are performed on modern equipment.

- The blade blank is cut from metal of the appropriate grade, in accordance with the drawing. After this, the blade is sharpened and polished.

- The next important step is the formation of a flat-concave “razor” wedge, which appears due to cuts of the surface of the blade from its back to the cutting edge.

- The necessary conditions for strength and reliability are hardening and tempering of the blade, for which electric furnaces are used. The hardness of the resulting blade is determined using a special table.

- Polishing is a mandatory procedure. Practice has determined the relationship between types of processing and surface roughness. The blade is polished to grade 10.

- If a design is intended to be applied to the blade, it is engraved and etched. To do this, the blade is varnished, the design is applied with a sharp metal stylus, and then etched with acid.

- In addition to throwing ones, a handle is made for other types of products. Traditionally, various types of wood or birch bark were used for it. It is believed that the handle should not only fit comfortably in the hand, but also not cool it, not injure it, and also have water-repellent properties. It is placed on the shank or attached to it using rivets. Today in production there is not only wood, but also modern durable and beautiful plastic and composite materials. If knives are made to order, the client can choose the one he likes, including various alloys.

- The backplate and guard are made from textolite and other materials using a casting procedure. An elegant guard for a gift knife can be made of an alloy with the addition of valuable metals.

- The final stage is the actual assembly of the product itself and sharpening the blade. It should fit onto part of the guard to a depth of 2 mm. Then the shank is attached and the elements are precisely adjusted.

- Sharpening is carried out on special equipment at a certain angle, depending on the purpose and model of the tool.

Features of steel knife hardening

Almost everyone knows that steel needs hardening.

Hardening steel is a process where the metal is heated to a temperature in the range of 750 to 1100 ° C, and then cooled sharply. Depending on the type of steel, different parameters of heating temperature and cooling medium are used.

Knives used in everyday life, hunting, and hiking must, first of all, be durable. A high-quality knife should remain intact, even if it accidentally falls and is stepped on. When hardening a knife, you need to pay attention to its strength, not hardness.

The blade of the knife should be hard enough, then the knife will not become dull soon, but not too hard, because then it can simply break.

It is not possible to determine the quality of hardening by appearance simply by looking at a knife. If the blade of a knife is not sufficiently hardened, it will often need to be sharpened during use. The blade of such a knife will be soft and easy to bend.

If the metal of the blade is overheated, such a knife will be fragile and can break very quickly.

The ease of working with a knife is affected by the degree of sharpening of the blade. The sharper the sharpening angle of the blade, the less effort you need to make to cut any material.

What are the common grades of steel used in the manufacture of knives?

The steel grade refers to its composition, which has its own rather strict standards. Based on the blade material, the knife can quickly corrode, require frequent sharpening, bend easily, or simply break under light load.

When purchasing knives, you should pay attention to the hardness of the blade. Most manufacturers indicate this parameter in their catalogs. In world practice, hardness is measured in Rockwell units and denoted HRc. It is recommended to purchase knives with a hardness of 40 to 60 HRc.

Making a knife yourself is a fascinating process; before you start, you need to know some of the features of steel.

Now let's look at the most common steel grades found in the production of knives:

- Steel 65G – used in serial and individual production. Steel is quite susceptible to corrosion, bends easily and can burst. To avoid rust, when producing knives in factories, the blade is coated with various polymer compounds. The advantage of 65G is the affordability of the material and good cutting function.

- Steel 40Х12 is quite soft. It is used to make knives for the kitchen and blades for souvenirs. This type of steel does not respond well to hardening. Despite the fact that knives quickly become dull and bend easily, they do not rust at all. These knives are quite easy to sharpen and do not require additional care. Having a knife made of this steel in the kitchen, any housewife will be completely satisfied with it.

- Steel 95X18 is domestically produced and does not rust. It has its own characteristics during hardening and processing. Knives from well-known manufacturers are highly hard, at the same time flexible and durable. After sharpening, the blade remains sharp for quite a long time. When using a knife made of 95X18 steel, it is recommended to wipe it with a towel after contact with water to avoid corrosion. If you make a knife from such steel yourself, you need to prevent it from overheating. Otherwise, the blade will become brittle and can easily break.

- Steel 50Х14МФ is widely used both by private craftsmen and on a production scale. The blades of the knives are strong and hard, and remain sharp for a long time, despite regular use. It is a good all-purpose steel, but can corrode when exposed to water for long periods of time.

Secrets of making knives yourself

The technology of making a knife at home requires some time and patience. You can make a knife blade from many available tools, for example, a flat file. From this affordable item you can make a knife that will become the pride of the owner and will serve for many years.

First, the workpiece is placed in an oven, fireplace, stove or wood fire, warmed up for several hours and left there until it cools completely. This processing method helps reduce the hardness of the metal for processing with metalworking or electric tools.

It is very easy to control the shape of the future blade using a cardboard template. It is impossible to imagine a knife without a handle. The most accessible material for it is wood. In order for the handle to be easily installed on the knife, holes need to be drilled in the tail part of the future product.

Before assembling, sharpening and polishing the blade, it should be hardened. At home, this can be done with a muffle furnace, a blowtorch or a small forge. When hardening steel yourself, the most important thing is to achieve the desired temperature. It is usually customary to be guided by a light cherry or raspberry color, which indicates that the workpiece is heated to approximately 850 degrees Celsius. The second way to check that the desired temperature has been achieved is the absence of magnet attraction.

Taking the knife by the tail with pliers, it is dipped into a solution of water and salt or waste. Since a hardened knife can easily split from an impact, it must be heated a third time to a temperature of approximately 300 degrees Celsius and left to cool slowly in the open air.

The handles should be fastened to the tail of the knife with rivets, after making leather gaskets.

At the end of the manufacturing , it remains to process it with sandpaper and further polish the blade.

" Making Knives" read 3712 times

Materials for making kitchen knives

Any knife consists of two parts: a blade and a handle. A good cutting object should have a high-quality blade and a comfortable handle.

Blade. Blades are now made from: steel (the most common material), ceramics (silicon is used - the same as on primitive knives), plastic (not disposable options, but sharp and durable with a blade made of composites).

Basic criteria for choosing a kitchen knife.

Let's start with steel. Many steels of varying hardness can be used for manufacturing. Steel is considered “good” if it has a hardness of at least 50 on the Rockwell scale. Standard stainless steels with good hardness are: 40Х13 (imported analogue - 420 steel), 65Х13 (440), 95Х18 (AUS 10). In Russia, blades are most often made from these steels.

The best of them and, naturally, more expensive, is steel 95Х18. Steels that are worse than 40Х13 are usually marked “Stainless.” (or Stainless on imported items). Knives made from the above steels are mass-produced using the rolling method. Some manufacturers use a laser rather than a rolling mill for hardening. As a result, laser-processed blades are much more expensive than rolled blades, but they have the “magic” property of self-sharpening when cutting food. Also, a forged blade is better than a rolled one; it is made by hand, but it does not cost much more than rolled ones.

Forged knives are made not only by large companies, but also by blacksmiths. Ceramic ones are the latest in culinary fashion - they are made from silicon. They practically do not dull, cost no more than steel ones, but have one big drawback - fragility. If it falls, the blade will most likely break or crack, and it is also possible that jagged edges will appear that cannot be straightened at home.

Plastic knives are very rare, but in some countries kitchen sets of such products are sold. The advantages of plastic options include lightness, good cutting and lack of dullness. The disadvantages include their fragility. It is especially worth noting that high-quality knives have a blade tang length no shorter than a third of the length of the handle, and ideally the tang should be the entire length of the handle.

Types of kitchen knives.

Handle. The most common materials for handles are: wood, plastic, elastron (special rubber), metal, textolite.

The most practical are elastron and textolite - they hardly wear out, are among the cheapest, their shape is carefully processed, making it most convenient.

Over time, wood begins to dry out and crack. To prevent this from happening, such a handle must be monitored.

Metal is used frequently, it is unpretentious to the conditions, but it adds extra weight, which reduces its convenience.

Plastic is used mainly on inexpensive knives and its quality is usually low - it crumbles over time.

Knives for production

Cutting tools are needed not only for personal use - in the industrial sector there are enough enterprises where these products are used for various types of activities: wood processing and the production of secondary materials from it, cutting and cutting metal, crushing plastic. They are divided:

- to guillotine;

- disk;

- flakes;

- chippers;

- combined and others.

Manufacturing knives for production is an important sector that supports the activities of many enterprises in various industries, including catering, medicine and others.

Blade material

Blade material

Every normal person knows from a young age that knives are made of iron, or more precisely, from an alloy of iron and carbon called steel. The higher the percentage of carbon in the alloy, the stronger and harder (after heat treatment) our steel will be. However, humanity did not always rely on this useful material, having managed to live vast stretches of its history with stone, and later with bronze blades in their hands.

Anyone who thinks that stone knives were so primitive and wretched that they are worthy only of ridicule from the heights of our atomic age is himself worthy of the exclamation from the old film: “Your lie, uncle!” In fact, stone tools are in some ways superior to the most modern materials, manifesting magical properties in unexpected areas. They owe this to their highest hardness, due to which the cutting edge is simply not capable of dulling, maintaining a degree of sharpness for a long (essentially unlimited) time that is inaccessible to metal. It’s clear that we don’t use cobblestones, and to make a high-quality stone knife we will have to acquire something glass-like. Volcanic glass (obsidian) and flint were considered the best raw materials. It has been experimentally proven that they are able to produce an edge of molecular thickness, that is, its sharpness is absolute

. Surgical operations using stone blades clamped in special handles were crowned with a brilliant triumph. The skin and flesh part as if on their own, almost without pain, and the wounds inflicted heal much faster, forming thin, unnoticeable scars. It is not surprising that modern gunsmiths are actively experimenting with ceramic blades of various compositions. As a rule, these are carbides with extremely high hardness.

A significant disadvantage of the stone is its fragility, which, however, is not at all bothersome under normal conditions

operation of the knife. Of course, if you get the idea to throw a zircon blade at an oak stump, you can say goodbye to it in advance. This is why stone knives are never long enough, and history has never known stone swords.

Bronze alloys appear in a fair variety, but the achievements of modern metallurgy do not excite us. The bronze that was used in the era of the same name is a simple two-component alloy of the necessary parts of copper and tin. Accordingly, such bronzes are called tin bronzes

. By changing the percentage composition, you can change the mechanical properties of the final product. In general, the relationship is as follows: the more copper, the softer the bronze, and vice versa.

It should be emphasized that the ancient masters penetrated into the unimaginable subtleties of their craft and used technological secrets that are unknown (or rather, lost) today. Unlike the manufacturing process of steel weapons, bronze weapons were cast into ready-made molds, immediately acquiring their final shape. But it was too early to fight with such swords, as well as to cut with knives - it was so necessary to skillfully and leisurely forge the entire blade, and especially the cutting edges, compacting the crystalline structure of the metal, giving it additional rigidity. And the cunning Chinese in all centuries managed to cast bronze swords with different tin contents along the edges and in the center of the strip. Accordingly, the main “body” of the blade turned out to be softer, not prone to cracking, and the blades were a little fragile, but hard.

The best bronze products known today are not much inferior to steel ones (if you don’t take truly unique specimens for comparison), and they have cut and stabbed the sons and daughters of the human race countless times. Over a long period of history, bronze and steel weapons competed with each other, and the superior technology of bronze often put the archaic technology of iron to shame. Let time and progress take their toll, but anyone who dares to consider bronze weapons as something amusing will be catastrophically wrong.

To conclude the topic, I suggest taking a look at a typical large dagger (or short sword), dating back to the 4th–5th centuries BC. e. Here you can also clearly see the original way of connecting the blade with the handle, which is characteristic of bronze products.

Steel, as stated above, is an alloy of iron and carbon. If the carbon content is over 2%, then we are talking about cast iron, although it also contains a lot of different impurities like sulfur, silicon, and so on. In fact, the boundary separating cast iron from steel cannot be marked by a clear line, since by mixing pure iron with 2% carbon, we get the so-called ultra-high carbon

steel, which is useless in itself, but is the raw material for the production of damask steel.

Moving down the carbon content scale, we have, respectively, high-carbon

(1.5–0.7%) and

low-carbon

(0.6% and below) steels. I repeat: the boundaries here are arbitrary and vague.

Of course, only high-carbon steel is suitable for making blades, which acquires elasticity and hardness after heat treatment.

Ideally, the amount of impurities in the alloy should be zero - such steel will have the highest possible advantages. But in nature there is no absolute purity, and different substances entering the melt ultimately give it properties that differ from the standard ones. Based on the nature of their impact, impurities are divided into harmful and beneficial, although this is also conditional. From the point of view of the weapons industry, phosphorus and silicon are not just harmful, but are a real poison for steel, increasing fragility and friability. But a whole class of so-called automatic weapons

phosphorus steels, which are used for mass production of secondary parts produced by automatic machines. They are not capricious and easy to cut.

Substances that clearly increase the mechanical properties of steels are called alloying substances. As a rule, alloying additives require tenths and hundredths of a percent, but this is enough to dramatically increase hardness, ductility, and the ability to resist shock, friction, compression and stretching, high and low temperatures and aggressive environments.

For centuries, the production of edged weapons operated only with carbon steels, and this was quite enough, including the traditions of cast and welded damask steel. But these days, metallurgy provides a rich assortment of alloy steels, which are initially superior to carbon steels in all respects. Considering that almost all of them are stainless, then it’s a sin to wish for better.

Almost all alloying elements are metals. Chromium and vanadium, molybdenum and tungsten, manganese, titanium, aluminum and a whole range of other, rarer and more refined additives, added in scrupulously precise proportions, give rise to amazing phenomena. It is believed (rather controversially) that the inimitable properties of Japanese blades are the result of the presence of some of the listed elements in the local ore (sand), but we personally did not have the opportunity to see documentary reports of spectral and other analyzes.

The most popular grade of steel among Russian gunsmiths is manganese spring 65G, pleasant for its availability and ease of heat treatment. Incomparably better results are obtained by using heat-resistant and heat-resistant steels classified as high-alloy. Especially for the curious, I present several brands of this kind, whose ornate names surpass even the names of Polynesian cannibals:

09Х17Н7У

45Х14Н14В2М

10Х11Н23ТЗМР, etc.

Those who are especially curious can open the directory and enjoy the long list of steels that they will never be able to obtain in their lives. This whole story is complicated by the fact that the heat treatment of such alloys is very sophisticated and requires at least special muffle furnaces with temperatures above 1000 degrees - only in such modes do high-alloy steels accept hardening, and many of them will gain extraordinary strength only after additional treatment with liquid nitrogen, then eat at ultra-low temperatures.

Making a multi-layer blade from alloy steel is extremely difficult, since it does not want to be forged welded, no matter what cunning fluxes you use. Only simple carbon steel is readily welded, and even then the more carbon, the more capricious. But not everything is so bad - an ordinary blacksmith is able to pull out an old valve stem into a plate, and then harden an almost finished knife in oil.

Having uttered the word “blacksmith”, we ourselves have defined the boundaries beyond which it is simply stupid to talk about blades. It would be worth repeating a thousand or ten thousand times - any

a normal blade of a knife, dagger, saber or sword must be

forged

and only forged. Such a problem did not exist a hundred years ago, but now, in the era of the triumph of rolling mills, it is easier to find a steel sheet of a given thickness than an ordinary forge with a forge, coal, smoke, etc. In principle, rolled steel is similar to forged steel - compressed in a hot state with On both sides, the workpiece is compacted and acquires almost the desired structure, but this is not enough. A tolerable, elastic and strong blade can be made from rolled sheets, but it will never reach the level of one skillfully forged on a simple anvil. The fact is that, unlike a rolling mill, concentrated hammer blows deform the crystalline structure much more intensely, also clearing it of impurities that seem to be “knocked out” away. In addition, from a sheet blank, a modern craftsman is forced to cut out the contour of the product in one way or another, profiling it and achieving the desired section by milling or grinding on abrasive wheels. That is, it simply removes excess metal, leaving the required part.

The situation is fundamentally different with the blacksmith: he does not remove the excess, but hammers

them into the blade, thinning it towards the blade and tip.

The product is formed from an initial portion of metal due to its compaction. As a result, forged blades, when compared with carved ones, turn out to be stronger and stiffer, easier to sharpen and keep sharpened longer, and are less likely to rust and break. That’s why it is said that a truly high-quality knife must have an individually

forged blade.

In addition, traditional technology automatically avoids the pitfalls that fatally await today’s craftsmen, even if they work in a modern factory forge. The trouble is that the workpieces are heated there in large gas furnaces, in the hellish heat of a roaring fiery torch. The uncovered pieces of iron lie there, heat up, and quickly lose their burnable carbon. As a result, instead of the original, for example, 1%, we get a pitiful 0.5%, enviable for nails and unacceptable for a knife.

At the same time, an old forge with a heap of heated charcoal not only does not burn carbon, on the contrary, in the upper layers the metal is intensively saturated with carbon, and in this way it is possible to obtain excellent steel even from ordinary iron. This is exactly what gunsmiths around the world have done for centuries, increasing the percentage of carbon and gradually bringing it to the desired level.

But technological progress has many false aces up its sleeve. The next one is that the widespread displacement of charcoal by hard coal, as well as coke, failed the weapons craft in the most fatal way. Both coal and coke (especially coke), with all their ability to quickly develop and maintain high temperatures for a long time, contain so much sulfur that the steel that absorbs it becomes completely unsuitable for blades. Therefore, anyone who decides to forge their own victory must absolutely and categorically acquire a bag of birch charcoal, pure and neutral, consisting of almost only carbon. Since in ancient times they did not know any other coal, they did not even suspect, lucky people, about such problems.

Before moving on to considering specific grades of domestic and foreign steels that have become common raw materials for edged weapons, it should be noted that there are a lot of rather vague, if not mystical, aspects in this matter. It would seem that the higher hardness of the metal definitely puts it at a higher level among blades - but no! When I worked as a graphic designer, due to my occupation I often had to cut with a knife sheets of so-called binding cardboard, made from the worst bark, which sometimes contained ordinary sand. And I had a working knife made from an old, Soviet-era machine saw. Perhaps the P18 steel grade tells the reader something, and its hardness was the highest. And despite all these delights, the wonderful knife had to be sharpened constantly, although neither by eye nor by touch did its sting become dulled at all - for some reason it just began to slide along the damned cardboard instead of cutting.

And so, having arrived in a gloomy state of mind, I once bought a banal shoe knife at a hardware store that cost a penny. I don’t know what steel it was made of or how it was heated, but it could be bent with your fingers in any direction, and it showed no desire at all to return to its original shape. However, the higher the degree of my indignation immediately after the purchase, the more genuine was the amazement when in practice it turned out that this soft piece of iron, being well sharpened, cuts, cuts and cuts the evil cardboard in the most magical way.

Then it became clear to me that the working qualities of a blade are determined not by absolute numbers of hardness on the Rockwell scale, but by some mysterious harmony of hardness and viscosity.

And further. Many of those who have to deal with scissors know what a torment it is when the capricious tool becomes slightly dull. Hairdressers especially suffer from the misfortune, especially since modern industry is by no means sophisticated in searching for rare grades of steel for the manufacture of household equipment. So, I have antique, early 20th century, German scissors, branded with a faded inscription and two Solingen “men”. They were left over from my great-grandmothers and were always found in the family, a little rusty, for all sorts of utility tasks like cutting tin, sandpaper and the like. Now, being slightly

(!) sharpened, they perfectly, incomparably easily and cleanly cut the most stubborn fabrics, felt, cardboard, from time to time they serve for haircuts and are not going to require new sharpening in the next fifty years. Yes, they are made of high-quality carbon steel and hardened to high hardness, but the magic that occurs cannot be explained only by this, and I, being some kind of expert in this field, do not undertake to comment on the amazing phenomenon. Simply put, the wonderful tool cuts everything, even when dull and jagged, while its modern brothers plague you with their finickiness, even when perfectly sharpened.

Now, moving on to a direct discussion of steel grades, we note the last nuance: given the specifics of the issue, absolute preference should be given to high-grade

qualities that are indicated by adding the letter “A” to the end of the name.

For example, 30ХГС, but - 30ХГСА, and so on. In this case, a more accurate ratio of components with a minimum content of impurities is implied. In addition, there is a whole category of so-called electric steels

, that is, produced in electric furnaces, in crucibles, without smoke and soot, with precise adherence to purity and recipe. It is not for nothing that sometimes people employed in closed military production boast of phenomenal hunting knives made from rare alloys inaccessible to mere mortals, which you will not find either in reference books or on the shelves of procurement areas of ordinary factories.

Finally, we have to take into account the realities of modern life, and they are such that the confusion of the post-Soviet years in Russian industry is also manifested by the fact that familiar, tried-and-tested grades (the same 65G) turn out to be unsuitable for the manufacture of blades due to catastrophic violations of the welding technology. Accordingly, craftsmen have to look for unspent reserves from those times when quality, at the very least, was respected. Particularly attractive are rarities from the forties and fifties, intended for the needs of the military industry. You don't have to be a historian to understand how

grandfather Stalin punished for all kinds of violations. Hence the result. One old master told me about the fantastic properties of large files made of the now unknown U15A steel, which were produced in small batches purely to supply defense enterprises. The blades they made were simply incredible.

So, only high-quality tool and other special (!) steels are suitable for the manufacture of piercing and cutting objects:

Carbon

- U7, U8, U10, U12, etc.

Alloyed

— ШХ15, 40Х, 40Х13, ХВГ, 65Г, 95Х18, ХВФ, 9ХС, etc.

High alloy

- 20Х17Н2, 12Х18Н10Т, Р6М5, Р18, Р14Ф4, etc.

All types of spring-spring, heat-resistant and heat-resistant steels are definitely suitable, but all types of structural steels are questionable. Suffice it to say that at the beginning of the 20th century, Dagestan gunsmiths considered used locomotive springs to be the best material for their famous blades.

Any normal reference book contains long lists and tables indicating steel grades, their composition and properties. The most important criterion for suitability is the maximum achievable quenching hardness. Figures below 50HRC do not suit us. If the steel meets this parameter, then its other properties are so closely related to the processes of forging, hardening, tempering and all others that there is no point in clinging to them in advance - a skilled blacksmith will do everything as it should, and an experienced thermal specialist will not let you down.

Since the astute reader has already understood what should be considered when choosing domestic steel, he can easily supplement his knowledge on this issue by studying any of the many special reference books. However, recently an increasing number of foreign-made knives have been put on mass sale, on which it is clearly indicated what material the blade is made of. If the manufacturer is unfamiliar to you and if it is not Puma, Marttini or Randall, then in order to avoid wasting money it is useful to have at least a general idea of the steel grades used outside of Russia. Take a look at the summary table (above) indicating the content of all the main components, as well as the maximum possible hardening hardness.

Almost all grades of steel that are used in the production of knives are presented here, but the most popular and widespread remains 440 steel, corresponding to our 65X13, from which (as well as 40X13) most surgical instruments are made, which is why it is popularly called “surgical”. As a rule, venerable gunsmiths for the manufacture of special, expensive piece products use rarer brands that provide better mechanical properties, primarily a combination of high (about 60 HRC) hardness with fair viscosity, but for mass production the proven and reliable “440” is sufficient .